Our History

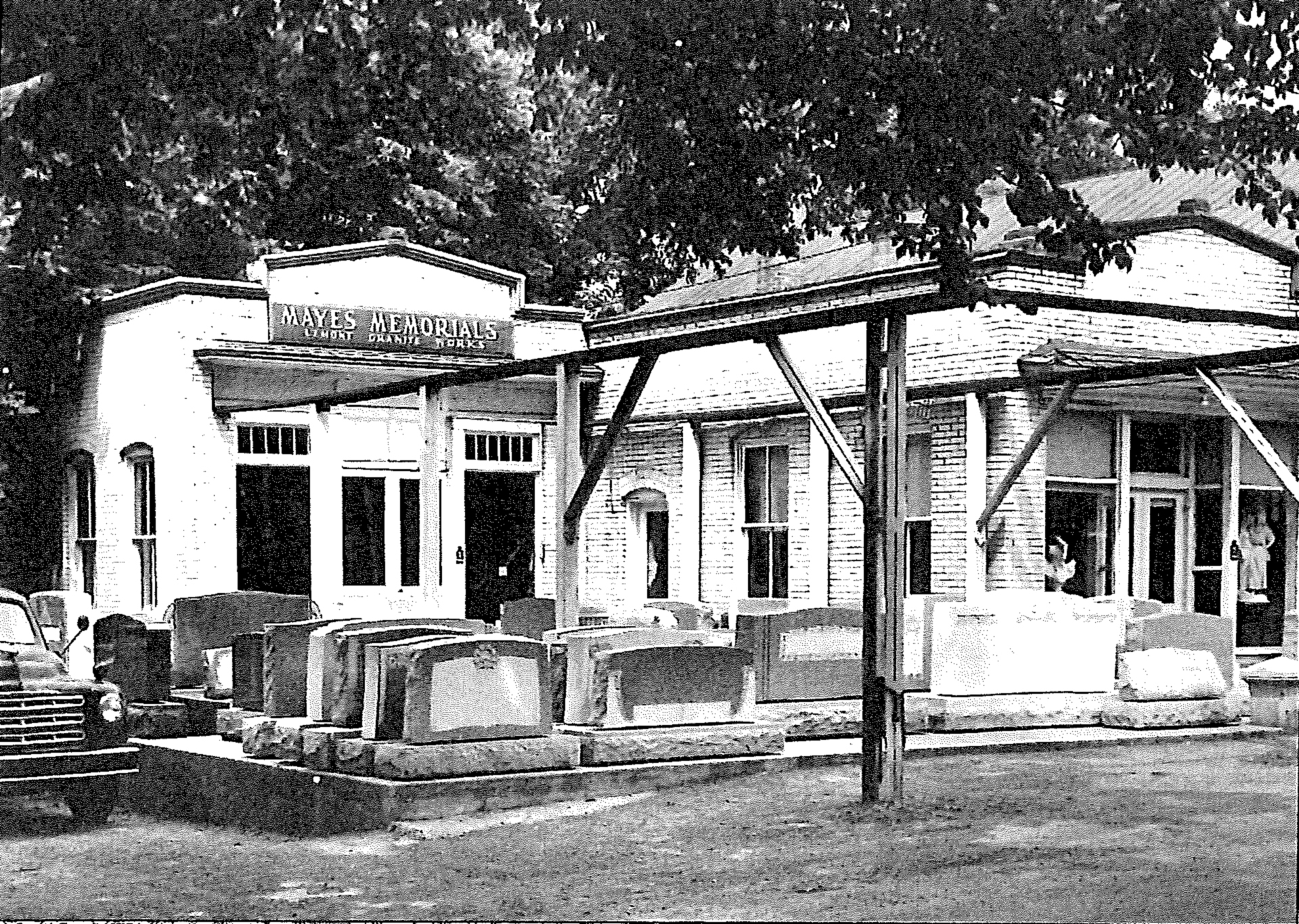

Mayes Memorials has been operating in Lemont, PA since 1900, making it the township's oldest continuing business.

Our company was founded in 1880 by Jones Berry Mayes, a stonemason who was skilled in the art of crafting tombstones. Originally known as Washington Marble Works and later Houserville Marble Works, the company that would become Mayes Memorials quickly became known for its quality workmanship and commitment to customer satisfaction.

Since then, and under new ownership since 1998, we have maintained the same level of commitment and become the leading provider of custom memorials and monuments in State College and the surrounding areas.

Making “Marble Stories”

By Donald L. Smith, Town and Gown June 1992

As his father guided the chisel through the mazes of an inscription, Eugene thought that his father's work would never be extinguished, that these letters would endure. - Look Homeward, Angel, Thomas Wolfe

When a social studies class at Houserville Elementary School was asked to write a brief biography of a fictional Civil War character they'd been studying, it was a near-perfect assignment for Brian Dague, for the biography was not to exceed fifteen lines written inside a tombstone-shaped border — and Brian's parents just happen to operate Mayes Memorials.

Although three generations of the Mayes family conducted the business in Lemont, it started near Houserville in 1880. That's when Jones Berry Mayes, owner of a wagon shop that had belonged to his father, John, decided to expand the business by selling gravestones - or "marble stories" as someone, probably poet Emily Dickinson, called them. For a time, he and George Wasson were partners in the Washington Marble Works. But within a few years George died and Jones Berry changed the name to Houserville Marble Works.

At the turn of the century, he moved the firm to Railroad Street in Lemont near the site of the present post office. "I've done some digging there," says Ron Dague, who owns Mayes Memorials with his wife, Lynda, "and found, about thirty inches down, what is undoubtedly part of the original building's foundation."

Jones Berry, who died in 1923, was known for his rectitude. "He made the Divine teachings of the Bible a guiding rule for his daily life," Bellefonte's Democratic Watchman said in a memorial tribute, and "he was an ardent advocate in the cause of temperance."

He was also the patriarch of a veritable monument-making dynasty. Four of his sons had memorial businesses in Pennsylvania - a fifth worked for a Vermont granite company-and a son-in-law ran a marble works in Bellefonte. The son who took over the Lemont business was L. Frank Mayes.

"As a boy," the township history explains, "Frank worked in ore mines operated by S. A. Brew at a wage of 33-1/3 cents per day. He and two of his brothers earned the tot.al wage of one dollar a day, paid to their father by check on the first of each month .... The sons were [later]. hired out to local farmers for nine months each year and their father collected all of the earnings except an allowance of one dollar per month."

In 1895, Frank drove a dairy wagon for M. M. Keller from Pleasant Gap to Bellefonte, but became a stonecutting apprentice to his father the same year. Later, he divided his time between family-owned firms in Houserville and Howard - the latter having been started in 1898 by his father and an older brother, J. Will Mayes.

In 1901, Frank married Lucy Keller, whose parents, Catherine and George Keller, owned the Houserville woolen mill founded almost 100 years earlier by Jacob Houser. Frank became his father-in-law's business partner, continuing in that role until he took over the Lemont operation after his father semi-retired in 1907, and ran it for the next forty years, at times with his son Ken as a partner.

Although the name Mayes was synonymous with memorials, Frank became even better known as an astute - and amusing - auctioneer. "He was a good conversationalist and very witty," says long-time pilot Sherm Lutz, a friend of Ken's. "He knew a lot of stories about people, and cracked jokes while auctioneering."

After his death in 1946, the Centre Democrat called him "a connoisseur of antiques" and a collector who "could rarely resist placing a bid or two on old clocks, canes, bells, and some types of antique glass." An equally good judge of human nature, "he sometimes laughingly said he could tell at a glance the main characteristics of a stranger." He had conducted sales at most farms in the county and "knew hundreds of countians by their first name."

When Frank died, son Ken returned to Lemont from Williamsport, where he had been purchasing agent for the Darling Valve and Manufacturing Company, and took over the business. Back in 1931, two years after graduating from Penn State with a major in commerce and finance, he had earned a pilot's license in a Texas school of aviation. Before going to Williamsport, he spent time in Niagara Falls, in charge of the Bell Aircraft School for Pilots.

Sherm Lutz recalls flying with Ken, and hoping Ken would work at Sherm's Boalsburg airport. Sherm also remembers Ken's fondness for cars: "He once owned a cream-colored one, and when you saw that car you knew it was Ken." That was an air-cooled 1911 Franklin, which Ken owned along with a 1931 Du Pont open phaeton. His daughter, Sandra Mayes Leitzinger, says he and Paul Houser of Lemont won a trophy with the Franklin in a rally-type race to Philadelphia.

Ken and wife Louise lived in the handsome corner house next to Mayes Memorials, a residence enhanced by roses and other flora that responded to the touch of Louise's green thumb. This was the same place where Frank Mayes had moved his family in 1911, when Ken was four. The Mayes home, currently owned by the Dagues, was built in 1870-71 for Dr. Jared Dale.

In these spacious surroundings, Ken and Louise — who did the bookkeeping and billing while he was busy fashioning gravestones or installing them in cemeteries — reared a son and a daughter. Today, L. Frank Mayes II resides in Georgia, and Sandra Jives in Harris Acres, not far from the Boalsburg Cemetery where her parents and other forebears are buried.

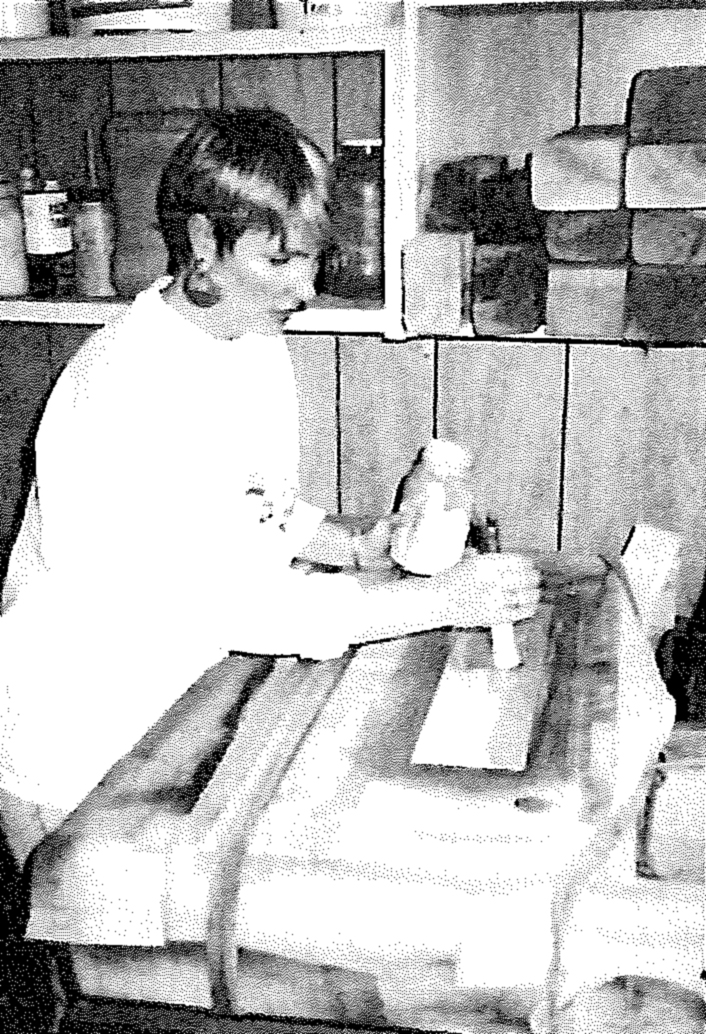

An internationally known water colorist specializing in paintings of race cars and antique autos, Sandra says the sandblasting process used in making tombstones is itself artistic. "It requires a fine eye and a steady hand," she explains. "Watching my dad at work helped in training my eye. When you're sandblasting or chiseling on a stone, you can't correct mistakes. You can't make mistakes while painting with watercolors, either, but it's even more true of preparing tombstones."

An internationally known water colorist specializing in paintings of race cars and antique autos, Sandra says the sandblasting process used in making tombstones is itself artistic. "It requires a fine eye and a steady hand," she explains. "Watching my dad at work helped in training my eye. When you're sandblasting or chiseling on a stone, you can't correct mistakes. You can't make mistakes while painting with watercolors, either, but it's even more true of preparing tombstones."

Sandra, a Penn State graduate in home economics journalism, says her father "took great pride in being fair in his business dealings. He showed respect for customers and taught us to treat everyone alike. He dealt sensitively with all kinds of people in times of sorrow, and thought it proper to honor the deceased with a stone. And on our visits to cemeteries, he had strict rules about never stepping on graves."

He retired in 1975 and died two years later, a month shy of his seventieth birthday, a victim of silicosis — a lung disease caused by years of inhaling silica dust from stone.

From 1976 to 1981, Mayes Memorials was managed by Ward McCall for the new owners, a consortium of several Central Pennsylvania funeral homes, one of which was owned by Ward's son-in-law. By the end of '81, the firm had been sold to Ron and Lynda Dague - a young couple originally from Reading whose main entrepreneurial experience consisted of starting the Cook's Nook in Calder Square, a business they owned for a year and a half.

"Our accountant knew we were interested in something else," Ron says, "and he told us about Mayes Memorials when he learned it was for sale. After I looked at the books, we talked it over and decided to buy it."

A 1975 Penn State graduate in recreational therapy who worked in psychiatric hospitals for several years, Ron did know a gravestone from a hole in the ground, but he knew nothing about how memorials are made. He says he's always been able to learn just about anything by watching, and his carpenter father had taught him a lot about concrete and woodwork. Prior to opening the Cook's Nook, he had been land-development supervisor for J. Alvin Hawbaker, and later, on his own, helped to build houses.

"Bill Mokle taught us how to do this work," explains Ron. "I don't mean just the mechanics of it, but also the proper attitude toward customers." Bill's mother was a sister of Frank Mayes, and Bill and his father used to own a monument company in Bellefonte. Bill also had done sandblasting and other work for his cousin Ken Mayes. Ron's basic education in the business consisted of working with Bill for several years, plus taking a month-long course at the granite company in Barre, Vermont, that is his principal supplier.

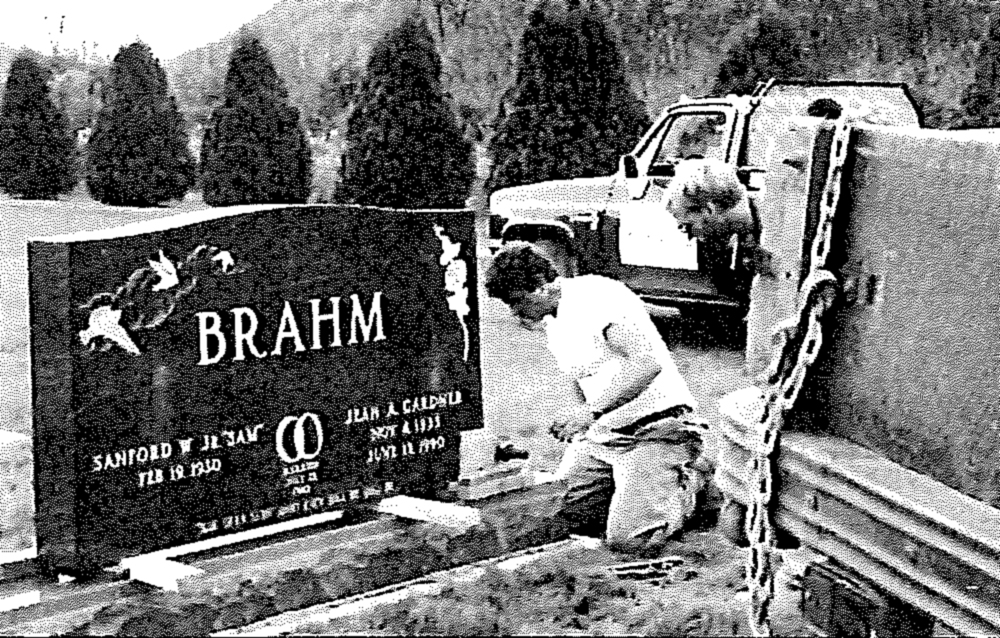

Some stones, Ron says, can be prepared in two or three hours, while others take two or three days. At the cemetery, stones are set on concrete foundations, which must be poured when the ground isn't frozen.

"One thing that will keep us a small business," Ron explains, "is that I go to cemeteries and do all installations myself. I also used to dig and pour all the foundations. I still do some, but Rick does most of that now.

"I like a stone to be level, and I use a four-foot level to check it," he explains. "After a stone is cemented in place, I clean up the site, making sure there are no fingerprints on the stone, reseeding the grass, and so on. And then I usually take a picture. I have a lot in scrapbooks to show customers." Interjects Lynda: "You've taken more pictures of tombstones than you have of the kids!" Their children are Ron Jr., fifteen, and Brian, twelve.

If Ron were in almost any other business, it might be said that he's "wrapped up in his work." Lynda conveys that idea in different terms: "You won't have any trouble getting information out of him. Once he starts talking about his work, he can't stop!"

For relaxation, Ron often joins the morning talkfests at Bill Williams' Barber Shop two doors down Pike Street. "Some days," Bill says, "Lynda has to come over and remind him it's time to get to work. He's a good guy and a hard worker with a nice family.

"I like to fish with Ron because he brings along a suitcase full of snacks; he's always eating. And when we go fishing, he doesn't like anyone else to drive. If somebody else is driving, he gets in the back seat, covers his head with a blanket, and sleeps. Says he can't stand to look."

Knocking back a can of soda as the afternoon winds down and an evening of work lies ahead, Ron concludes, "Patience heads the list of qualities required. There's a lot of creativity involved, and 'eye' is very important. Bill Mokle taught me to appreciate quality work, and Lynda shares my pride in carrying on the Mayes tradition.

"When I finish installing a stone in a cemetery, I step back and admire my work," he continues. "Sometimes I say to myself, 'That will last forever.' Well, not forever, which is a long time, but maybe for thousands of years!"